Better Streets for Kids: Fixing US road safety education

The following is an adaptation of our presentation at the 2021 Safe Streets Summit.

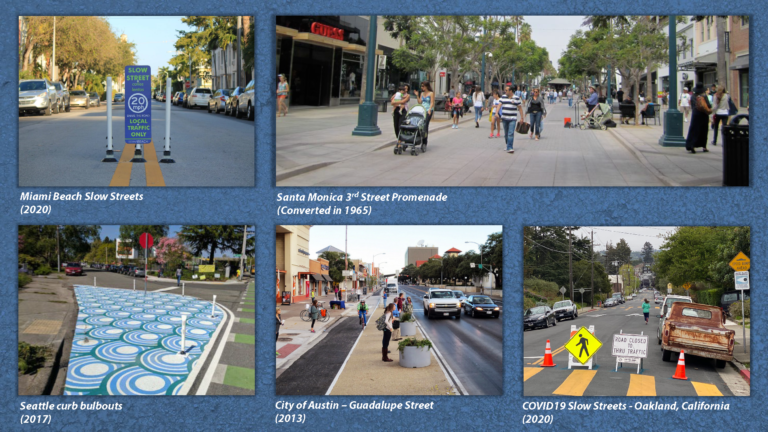

As many advocates and planners are aware, street engineering – after many years of prioritizing automobile speed here in the US – is evolving towards safe systems design instead; design, of course, that makes it difficult for drivers to speed or make a mistake that’s life threatening to others.

Streets of this design are often called Complete Streets – as they are here in Florida; sometimes they’re categorized within a holistic Vision Zero approach, and temporary measures are often called Tactical Urbanism. Regardless of the name, the end goal is to achieve the same thing.

However, the narrative that pervades road safety education to kids, parents, and the general public often do not reflect these efforts. If anything, they heavily reinforce the outgoing idea that drivers have unquestioned priority, and that pedestrians and other vulnerable road users bear the majority, or equal responsibility for crashes.

We can’t emphasize enough that the responsibility is not equally shared:

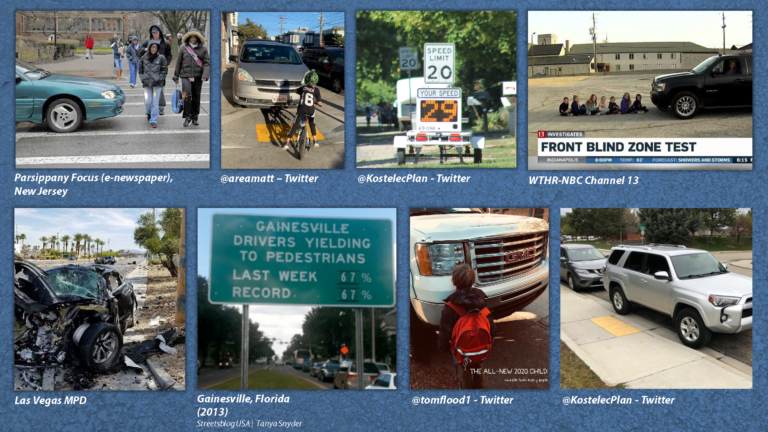

These images aren’t isolated incidents – they’re real examples of the dangers facing vulnerable road users today imposed by infrastructure that makes it easy for drivers to break the law.

These imbalances in both the danger and messaging posed to vulnerable road users vs. automobile users are correlated by case studies, scientific research, and the experiences all of us have had at one point or another on foot, in an attempt to cross the street.

There’s a historical reason this messaging perseveres.

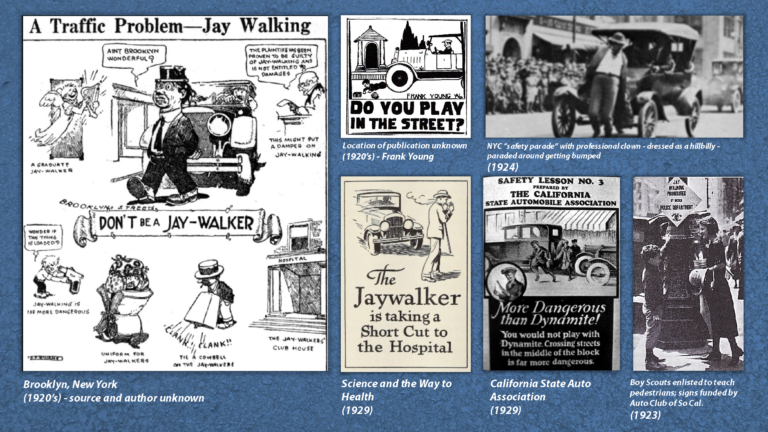

In the 1920s, the auto industry – eager to appropriate mostly pedestrianized roads for themselves – launched expansive campaigns against pedestrians crossing mid-block – what was then newly-coined as “jaywalking.” These campaigns were accusatory and offensive, designed to socially engineer society into accepting that the automobile was the unquestioned heir to the street.

There were converse campaigns and newspaper articles that pointed out the safety imbalance – especially for kids. Still, the few campaigns that existed were not backed with the same budget – so this message wasn’t heard with the same frequency.

The social engineering…worked.

As the car was normalized, these messages were sanitized and given the Leave it to Beaver treatment, giving us the squeaky-clean “look before crossing” and “watch for cars” messaging of the 1950’s. They still placed onus on pedestrians – especially kids.

While some may think this is a heavily cynical take on the matter, even comedian Adam Conover – who discussed this exact topic on his truTV show, Adam Ruins Everything – noted that these messages have prevailed mostly unchanged today, even though the gist of them are at odds with safe streets and the principles of Vision Zero.

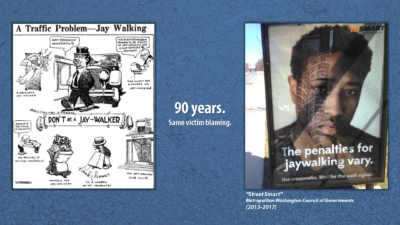

As a result, despite the evidence and research behind safe streets, a large portion of PSAs and campaigns produced today are simply modernized versions of the same, subtly degrading messages. Some of them are almost as offensive as those from the past.

The problem is that we’ve been born into this messaging. We’ve likely received it as children ourselves – and repeat it without questioning it.

Though it’s not bad advice to keep an eye out for reckless drivers – particularly on streets that are inherently unsafe – those involved in promoting road safety have no business continually normalizing and excusing this driver behavior instead of promoting measures leading to that street’s redesign.

This continued skewing of responsibility is not only a knowledge problem, but a huge barrier to getting safe streets built. Case in point, in Miami, many cannot fathom the idea that there is any alternative to more lanes and faster speed limits; having lived with them for so long. The suggestion of safe streets tends to get rejected, out of fear that their livelihood will become even more difficult.

It’s only worse if somebody’s first encounter with safe or slow streets comes as a relative surprise through a public meeting. We’ve seen funded projects die due to this fear, compounded by the lack of political will to consider safety over the status quo. No less than a double whammy of working against the aforementioned social engineering of car-centric thought and general human nature of fearing change.

Put simply, it’s not just the infrastructure; safety messaging – from all sides – must undo the damage of history.

We must encourage forth new narratives that champion the person on foot in need of a safe crosswalk, the person who uses a wheelchair in need of an adequate-width sidewalk, or the person on a bicycle in need of a protected bike lane.

But what could education about infrastructure look like, especially if someone isn’t a planner or engineer?

It could look like this:

It could also look like our new Better Streets for Kids module in our WalkSafe Virtual Education lessons, which discusses forward-thinking street design based on the Federal Highway Administration’s PEDSAFE Countermeasures:

While topics like these are usually discussed only on a professional level amongst engineers and planners, the concepts behind them are easy enough to understand – allowing us to basically present them to families in the format of a digital kid’s picture book. Importantly, this education teaches both to envision their neighborhood with safer streets, rather than accept more messaging that scolds kids for existing in the hostile car-centric environment we have today.

Good campaigns like these are slowly beginning to gain traction. And the more of them that people begin to hear, the more people will begin to question the automotive centric status quo set 90 years ago – and think about safety instead.

Mind you, we’re already at a point where Jalopnik – the online automobile news site whose slogan is literally “Drive Free or Die” – is publishing articles criticizing NHTSA and auto manufacturers for shifting blame to pedestrians.

Finally, let’s not forget that actual action to change these streets is more important and effective than any messaging campaign. Sure, the campaigns can help undo the social engineering of yesteryear, but no amount of asking drivers to behave is going to matter to those who aren’t willing to change their behavior. Our streets have to prevent this behavior in the first place – and give space back to our kids.