Why we are concerned about Miami’s Critical Mass:

This week’s Twittersphere has been humming with speculation, following rumors that the City of Miami Police Department may considering rescinding support of Critical Mass.

Hey @MoralesMiamiPD I’ve ridden #CriticalMass with my then 16 year old daughter and my 70+ year old mother. It’s fun. It’s healthy. The support of @CityofMiami Police is important. @FrancisSuarez https://t.co/J12EKzQnP5

— Miami City Man (@miamicityman) March 23, 2019

We’ve been reading and thinking about this too – and we have a dilemma.

Like it or not, Critical Mass is more than just a bike ride or a traffic disruption, it is an element of bicycle advocacy. Though some of us are not fans of the confrontational approach some riders take in Critical Mass rides, we are always concerned that both bicycle advocates and bicycle advocacy receive fair treatment as a whole.

So what is so good – or bad – about Critical Mass?

Depending on where you’ve been and when you’ve come across one, Critical Mass can be anything from a gigantic assembly of everyone and anyone imaginable on a bicycle, or a relatively small ride with – once again – people from all walks of life.

That doesn’t sound so bad, does it? It sounds like a “big bike ride.”

In some ways, that is what it is. Yet, history has made it more than that. To understand why, one has to realize how complex bicycle advocacy is here in the United States:

Since the ’60s, bicycle riders have generally been expected to ride with automobile traffic; either at the edge of the road, or in the middle, “claiming the lane.”

At the same time, other countries were experimenting – and eventually standardizing – separated bike lanes and facilities, giving people of all ages, occupations, and lifestyles the option of using a bicycle for transportation.

Yet, most American cities eschewed this equitable approach (with notable exception to Davis, California), as many planners and road cyclists of the time sided with the writings of John Forester – a theorist and road cyclist who contends that separated infrastructure puts the bicycle rider beneath the motorist for priority and respect.

Today, we know this argument is false from multiple points, including funding for bike facilities, bicycle encouragement, drivers’ perception of riders, and especially safety.1

But old recommendations die hard. Nearly 50 years later, there is no great concern to rectify this error.

As such, bicycle advocacy in America, over the last 20 years or so, has been the road safety equivalent of a Rodney Dangerfield punchline.2 Unsurprisingly, many riders are indignant about this and do not mind bending the rules with good intentions.3

And from these advocates emerged Critical Mass: A pseudo-protest ride over the state of US streets that grew into a phenomenon.

Today, an established Critical Mass can be thousands of people on bicycles, but since the ride has always been without definition or purpose since its inception, anyone can impart their own agenda on it – for better or worse.

Want to ride your bike without worrying too much about cars? Ride with Critical Mass. Want justice for bicycle riders? Ride for it at Critical Mass. Tired of drivers treating you like a target on the road? Cut ‘em off at Critical Mass. Want to blend into the masses while drunk as a skunk? Booze it up at Critical Mass – there are no bouncers at the door.

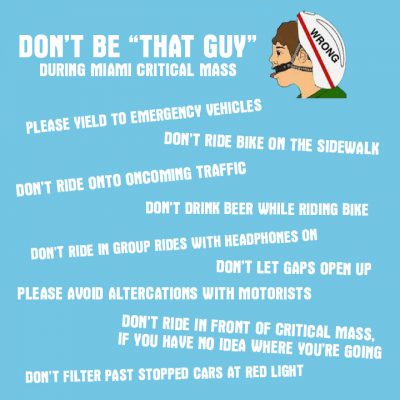

See what we mean? It’s a bike ride, but a few individuals with confrontational agendas can create a black mark on it. As the Miami Bike Scene blog often points out, ”that guy” is the one who can ruin the ride for everyone – and advocacy.

The Miami Bike Scene’s “Don’t Be ‘That Guy'” flyer

History lesson aside, the problem is that we do not consider these issues from the standpoint of the one individual person on the bicycle that is causing trouble; instead, the whole Mass – and bicycle riders in general become targeted as a problem by local media and law enforcement – completely missing the point about the original point of the Mass (treat bicycle riders with respect), and how we view road safety incidents in general (drivers are rarely lumped into a single group after one person breaks the rules).

Thus, when a city takes actions for or against Critical Mass, these actions directly affect perceptions about all bicycle riders, and can unfairly encourage broader punitive action. Other group rides – or bicycle users in general – can become targets.

For instance, in NYC, any group of 50 or more people on bicycles are at risk of being ticketed or arrested without a parade permit.4 In some bicycle-friendly cities – even those here in the US – rush hour traffic on their protected bike lane networks would easily constitute an assembly of over 50 bicycle riders. Legislation such as NYC’s opens up a possible loophole to people’s civil liberties in this scenario.

Remember that quandary we had at the start of this article? It should be clear now. While we’re not fans of the confrontational approach some riders may bring to Critical Mass rides (once again, to be clear, these are the actions of individual riders and not the mass itself), it has grown into something much more mainstream than its origins. How our cities approach the Mass can and will affect advocacy as a whole. As such, it should be handled with the greater good in mind.

We can understand the reluctance to support an event that has the potential to get out of hand by virtue of a few bad apples or impatient drivers, but these individual bad actors don’t necessarily represent the Mass either. There are families, kids, and people just wanting to partake in the one group ride in Miami that doesn’t have any barrier to entry, and these participants do not deserve to be victimized for their desire to participate in that once-a-month ride where they can feel safe on our streets.

In other words, Critical Mass still remains a community bicycle ride, and deserves careful consideration and support – especially from law enforcement, who have the unique ability to help mediate any conflicts when they happen.

So what to do?

The only thing that could soften any reduction of Critical Mass support would be an increase in bicycle facilities as a gesture of goodwill, such as the protected bike lane concepts that Transit Alliance Miami suggested for Biscayne Boulevard.

Otherwise, it is best to make Critical Mass work in favor of the city and bicycle advocacy, using it to bring about better and safer places so people can ride in safety, thus finally demonstrating to the public that our County and City is committed to equitable road infrastructure.

Think about it: Critical Mass is a physical manifestation of people relaying one of Freddie Mercury’s most famous song lyrics:

“I want to ride my bicycle.”

Why fight that?

- See: https://peopleforbikes.org/green-lane-project/inventory-protected-bike-lanes/

- “…I get no respect!”

- Case in point: We would have never seen things like sanctioned tactical urbanism happen if advocates had not first bent the rules by creating tactical urbanism projects without cities’ approval. We’re not condoning this, but the evolution of change speaks for itself in history.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/17/nyregion/17bike.html